YANOBE KENJI 1969-2005

03 SURVIVAL x RIVIVAL [1997-2003]

【Chapter 03】1997-2003 SURVIVAL x RIVIVAL

Yanobe continued to build devices for his own survival as part of his “Delusion”. He became aware that the point of departure for his creations was his simulated experience of “Time Travel to The Ruins of the Future” at the 1970 Japan World Exposition (Osaka Expo) during his early childhood. Yanobe’s visit to Chernobyl enabled him to recover his sense of reality. It also was a trip to experience the primal landscape again.

Yanobe discovered the point of contact between “Reality” and his world of delusion and returned to Japan to open “The Lunatic Park Project – The Last Amusement Park of the World”. He again continued to produce creations based on the theme of “Survival”, further enhancing a world of delusion that contained a hint of fin de siecle.

Before the end of the century, Yanobe resolved to end his travels for “Survival” that he had continued throughout his career. He began to seek his next theme that would breathe new life into the world of delusion.

THE RUINS OF THE FUTURE

Immediately after returning to Japan, Yanobe opened “The Lunatic Park Project -The Last Amusement Park of the World”. Commonly known as the Luna Project, it was exhibited at the Kirin Art Space Harajuku, the Mitsubishi-Jisho Artium, and the Kirin Plaza Osaka.

With the inspiration he received in Chernobyl, Yanobe again created works based on the theme of “Survival” at the end of the century. These included the shelter-type dwelling based on Noah’s Ark and the vending machine that contained various items for survival. He also held as an attraction “The G.1 (Geiger-Muller One) Grand Prix Survival Race” with bumper cars capable of detecting radiation. The Atom Suit Pr0ject was displayed on a light box as propaganda for an amusement park; the film was shown at a movie theater. Created by Yanobe, who had recovered his sense of reality, these devices also were meant to expand the world of delusion for the end that was to come.

The Atom Suit Pr0ject was conducted later as part of the project to build “The Last Amusement Park of the World”. Yanobe chose different concepts for his projects, including the desert and a time tunnel. His last choice for a theme at this time was the former site of the Osaka Expo.

While recovering his sense of reality by traveling to Chernobyl, the existence of an amusement park in the ruins of a town was the decisive factor that guided Yanobe to the extent that he became obsessed by it. Yanobe has declared that the motivation for his trip was not the social problems of atomic energy or a nuclear power accident, but rather an individual impulse. The backdrop to this was another motivation: the unusual experience of seeing “The Ruins of the Future” as a child at the deserted site of the Osaka Expo. This important event was the source of Yanobe’s world of delusion.

Yanobe was born in 1965 in Osaka, and he was one of those who spent his childhood nearest the Osaka Expo (the 1970 Japan World Exposition). He has only fragmentary memories of the Expo when it was open, however. He reports that he learned about the excitement and energy adults had for the future from the many Expo goods and photos in his home. Rather, the experience that had a stronger impact was visiting the Expo site when the exhibits had been taken down and removed.

Soon after the Expo ended, Yanobe moved to Ibaraki City near the Expo site. This site became his favorite spot to play as he watched the exhibits and pavilions being dismantled and removed. He and his friends explored and watched as the iron ball struck and demolished large pavilions. He snuck up onto the large roof where the height paralyzed him with fear. He also looked at Deme, a giant robot that had been discarded in the festival square.

Yanobe discovered “The Ruins of the Future” here, and he had the simulated experience of time travel. He felt a sense of expectation and mission regarding the land of the future that had sadly met its end and become a vacant lot. Yanobe wondered what would be created in this large area where everything had disappeared. He felt as if he had to create something, and that he could create anything because everything had vanished. This indeed was the point of departure for Yanobe’s creativity, as he continued to make devices and tools based on the theme of “Survival” for his own survival in a state of delusion.

For Yanobe, the realization that his experience of time travel to “The Ruins of tbe Future” at the former site of the Osaka Expo was tbe starting point for his creativity was tantamount to having received a divine revelation. He thought that if he could have another identical experience he might be transformed again. He then launched the Time Travel to the Ruins of the Future Project. He wore Atom Suit and undertook his trip to Chernobyl, which symbolized “The Ruins of the Future” in tbe present day.

Yanobe left Berlin in June 1997 for Chernobyl. This city lies to the north of Kiev, the capital of the Ukraine. In April 1986, there was a meltdown and explosion of the nuclear core in Reactor #4 at the Chernobyl atomic power plant, destroying the building. This was recognized as a Level 7 accident according to international standards, the worst type of accident that could occur. The accident unleashed an estimated several hundred million curies, equivalent to several hundred times the force of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. In addition to the many casualties, it spread radioactive contamination to countries throughout Europe and the world.

The area within a 30-kilometer radius of the nuclear reactor (which was forcibly evacuated) is called the Zone, and entry is prohibited. There is also a facility called the control post 10 kilometers from the reactor controlling entry and exit to ensure that contaminated material is not taken from the area. In 1996, 10 years after the accident, journalists from several countries wrote articles on the incident. One year later, howevei; few people visited the site. The nuclear reactor next to the one where the accident occurred is still in operation. The workers at that reactor board a bus every two weeks to enter and leave the Zone.

Yanobe entered the unknown territory on the other side of the red and white barner. The amusement park was in Pripyat, a city about three kilometers from the reactor. It is reported that several days after the accident, an orderly evacuation of the city’s residents was conducted without panic. The people were told to evacuate in three days, but the city was still a ghost town 11 years after the event.

Dressed in Atom Suit, Yanobe, who resembled an alien that had arrived on Earth unnoticed, entered the amusement park. He boarded the Ferris wheel and the bumper car, becoming a spectator at the park, no longer in operation, and occasionally smiling behind the round visor of his helmet. Suddenly, he received an unimaginable shock. He immediately broke off his trip to the destroyed amusement park that had been the purpose of his trip. The course of his journey was taken in a totally unexpected direction. He met Bakudan, a three-year-old boy. Yanobe had come face to face with the “Reality” that people still lived there. Shortly after the accident, the residents within a 30-kilometer radius, in addition to those from Pripyat, were forced to evacuate. Some who complained of the hardships caused by living in a different environment returned to live in the village they had grown used to, however. Most were elderly or pensioners, but one child had to return to the village to live with his mother after his parents divorced. Yanobe played in the sand with him. He showed Yanobe a cute kitten.

Chernobyl was in a natural setting surrounded by forest. The bounty of the forest, including wild mushrooms and strawberries, were an important part of the daily meals of the area’s residents. But eating these was forbidden after the accident, and the collective farms of the past had disappeared. It was dangerous to both eat and drink the local water. The environment had never been so harsh for the children. Yanobe thought an invisible shadow would sneak up on them. Yanobe, unable to stop the spread of the contamination and the damage, felt angry and disconsolate.

Gripped by panic, Yanobe continued to take pictures of the junkyard for helicopters and tanks that had extinguished the fire at the time of the accident, the landfill for contaminated waste, and the ship that had sunk in the river. Russian officials always accompanied him in the Zone, and they limited the areas open to the public and monitored his photographing.

Yanobe said that when he entered the devastated kindergarten, he strongly sensed the faces of the children. In one room where many beds were lined up, toys no longer used on the playground were thrown inside. These included dolls, wooden horses, and pianos.

As he walked through the towns and villages, Yanobe had to meet the people there. Most were elderly and very kind, and he says they welcomed him as guest from a far—off country or as a friend. There also were people who were angry at Yanobe, wearing Atom Suit, including drunks who thought he had come to make a laughingstock of them, and they tried to hit him. Yanobe measured some of them with the Geiger counter, and some of them registered a low level of radiation. They lamented that they couldn’t live with their grandchildren despite the safe level of radiation.

Yanobe’s struggles with himself continued, as he wore Atom Suit and stayed for a little more than a week as a form of self-expression. His encounter with the people had an impact more intense than he could tolerate. Still in this confused state, he ended his trip. Then he sealed Atom Suit N0.2, which he used for his trip to Chernobyl, in a lead storage box.

“Atomic power was formerly seen as the symbol of hope for the future, as was the Osaka Expo. That idea was destroyed with Chernobyl. We have lived in the crevice between prosperity and decay.”

The worldview of “Delusion” was created from the abandoned site of the Osaka Expo, which showed “The Ruins of the Future”. In the instant that worldview intersected with “Reality”, the Last Amusement Park of the World was created. This came into contact with the “Reality” of Chernobyl and was an artificial device for pleasure expressed by passing it through his own filter.

Unlike his previous developments, which were an invasion of the art world that became a kind of attack, Yanobe created an ironical exhibit that overlapped social phenomena rather than being entirely fictitious. At a glance, visitors could actually use many of the creations on the site the same as with the playground equipment of an amusement park. Those equipment, however, allowed visitors the vicarious experience of contradiction, in which an optimistic sense of trust was presented in contraposition to a scientific and social structure in a state of critical danger in a fin de siecle age.

Yanobe later launched several projects, attempting to promote both his own internal growth and communication with people through his works while continuing to form a communion between “Delusion” and “Reality”.

The structure of Yanobe’s world gradually began to expand to the age of “Reality” with the age of “Delusion” as its axis. At that time, as before, Yanobe could only ruminate while remembering the event at Chernobyl and his meeting with the people who lived there. For the artist, however, the end of the world was an expression that showed that negative and positive were two aspects of the same thing. This implied the beginning of the world in addition to a sense of conclusion. The delusion that was created from”The Ruins of the Future” was by no means an end-it engendered in Yanobe a sense of the potential for new creation.

ANTENNA OF THE EARTH

A nuclear power reactor accident occurred in Tokai-mura in September 1999. Yanobe, who participated in an exhibition held one month later, conducted the Survival Gacha-pon Project. (This was a workshop held at the Ground Zero Japan exhibit at the Art Tower Mito from 1999 to 2000.) In this project, a nationwide solicitation was conducted to find the smallest, most important capsule in the world. After a public presentation at the museum, Yanobe purchased the capsule he liked the most and incorporated it as an item in Survival Gacha-pon.

Through this workshop, Yanobe meet a woman living in Tokai-mura who said that she wanted him to come to the village wearing his Atom Suit. He was not able to do so. Yanobe, who had traveled to Chernobyl on a personal odyssey of experiencing once again “The Ruins of the Future”, was not able to give a social meaning to Atom Suit. Just at the time when he was looking for a way to go to Chernobyl, he was advised that the trip would be facilitated if he joined with the Greenpeace ecological organization. He declined because he would be rendered incapable of an expressive act passed through his own filter.

Later, Yanobe did actually visit the woman in Tokai-mura, though he didn’t wear his Atom Suit. He had purchased her capsule, and the capsule held the written request that people come to see the reality of the village, because it wasn’t that frightening, in addition to a pass for free lodging at her house.

In 2000, humankind passed through a prediction of Nostradamus. At the end of the century, Yanobe unveiled the Atom Suit Project: Antenna of the Earth as if to terminate the flow of “Survival”. He methodically arranged as many as 500 dolls with Atom Suit in a large area. Of these, several were attached with Geiger counters to detect the natural radiation occurring at random. On a pedestal in the middle of the space, Yanobe placed many photographs recording his visit with the people of Chernobyl. A doll of Yanobe himself, modeled after a standing statue of the Buddhist saint Kuya, was placed wearing Atom Suit with the helmet in its hand.

Kuya broke through the practices of Buddhism that had no connection with the people of his time. As part of his approach to himself as an artist, Yanobe overlaid his form on that of Kuya, who always lived with the spirit of the people for his mission and salvation. The artistic expression of removing Atom Suit helmet was to reveal his own life, as if to expose that which was within himself.

Yanobe had seen more “Reality” than he expected at Chernobyl. His anguish and conflict continued over whether to release these experiences as his artistic expression. But, he released an illustrated diary of his travel experiences and photos of the people he met at Chernobyl. He sensed a new potential that many people could enter through those works and expand in different directions through the vicarious experience of this trip. Yanobe said that he created Atom Suit with the image “of a distant existence of an alien, something possessed by a spirit, or something like that objectively watching the movements of the Earth and the acts of humankind.” While Atom Suit was like Yanobe’s portrait, its existence brought people together, because anyone could wear it, not just the artist himself. He then removed Atom Suit from himself and completed the story of the Atom Suit Project as a gift of hope for “The Ruins of the Future”.

After his experience at Chernobyl, Yanobe remarked, “I have a feeling that the work itself was not created by me, but by the world.” He renewed his idea that being able to continue to create new works, releasing them, and living his life was not a matter of his talent and luck. It was nothing more than being given a role from some larger, invisible existence.

Yanobe had sensed another attraction in the Geiger counter that he had attached to Atom Suit. In addition to the function of detecting radiation and the problem of the atom, another matter of interest was the idea of fate from the random radiation received. A small Atom Suit with an antenna received messages existing in nature and tried to convey something. Yanobe said it was important to raise a sensitive antenna while he constantly maintained a neutral state as an artist in that role. Antenna of the Earth was an installation that included this sentiment of Yanobe.

STANDA

As an extension of his trip to Chernobyl and to rediscover something by pmmng down the “Reality” within himself, Yanobe conducted “The Robinson Crusoe of 1999”. This was in 1999 at ICC with the workshop Symbiosis with the Evolving Robots for the exhibit called Co-habitation with the Evolving Robots. Yanobe began living with a robot for a week in a hut set up in a room at the museum to experience in public the cohabitation of the last member of humankind on an uninhabited island with a robot equipped with artificial intelligence.

His direction was the opposite from that of the robot’s growth, however, and he gradually suffered a nervous breakdown as he lived his life constantly observed by robot researchers and museum visitors. Finally, Yanobe concluded his experiment by wielding an axe and staging a drama of escape from his blockade by breaking through the walls of his hut. The entire time, which was a type of human experiment, Yanobe could not sense a spirit, life, or love in the robot. During the course of the exhibit, however, a small insect fell in front of him while he was keeping an illustrated diary. In the instant he observed it walking, Yanobe had a great sensation of the presence of life deep within and around that small creature. With the dawn of the 21st century imminent, a change began to appear in Yanobe’s state of mind as the tenor of the times also changed. He had created devices on the theme of “Survival” to protect himself, but he sensed a limit to continuing to present a worldview from a fin de siecle perspective. Yanobe began to discover his next direction, wondering whether he could achieve a more positive expression in contrast to global conditions, which had actually become disquieting.

At just that time, Yanobe’s first child was born. In the same way that he thought he must begin his life over again from the start, Yanobe himself discarded the theme of “Survival” that he had developed until then. With the dawn of the new century, Yanobe shifted to themes and activities that would bring a bright hope to the forefront. Then, in the Viva Revival Project, Yanobe unveiled Standa.

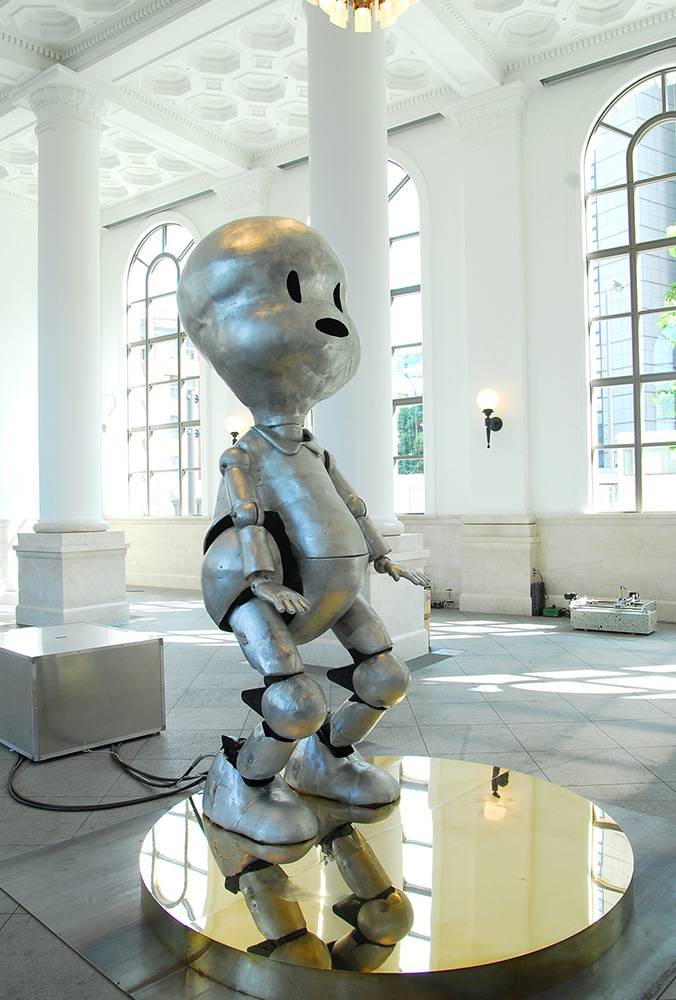

Standa was a three-meter-high doll that could stand on two legs. When the attached Geiger counter detected a certain level of radiation, it slowly stood, and then fell over again and stared at the mirrored surface of the platform on which it was placed. There was a mechanism in which the yellow Sun, directly in the doll’s line of sight, blew a bubble from its mouth in celebration m the instant the doll stood up.

Among the photographs of the kindergarten taken in Chernobyl, there was the form of Atom Suit picking up a doll that had been thrown on the floor under a picture of the sun that had been drawn on the wall. Using that photo as a motif, Yanobe began to create Standa to revive that doll and to link the giant step of standing on two legs in the evolutionary process of humankind with the growth stage of his own child. Yanobe’s conception of Standa came up against difficult physics problems during its creation. It was a jointed, three-meter-long doll (robot) that stood. He sought advice from a professor of engineering and a robot researcher, but he was told it would be technically impossible unless he reduced the scale of the doll. Conversely, this unleashed Yanobe’s spirit of creation, and he performed repeated experiments. He said that the production site was so dangerous he thought fatalities might result, as with every failure the doll collapsed with a terrifying force. Different specialists and technicians from various fields came to help, including an older factory worker in town who left his job to assist in the project. Gradually, some encouraging signs began to emerge.

At dawn on the day the exhibition was due to open, Standa finally stood up. On that same day, Yanobe’s child pulled itself up and stood for the first time.

Yanobe completed Standa in 2001 as a monument to “Revival”, the recovery of “The Ruins of the Future” in Chernobyl. It enabled the artist to incorporate the event at Chernobyl, and in that instant freed his artistic expression. The ritualistic act of standing on two legs and toppling over was as if Yanobe himself were headed toward “Reality” with his hopes and dreams for the future, or internalizing the conflict with uneasiness and dread. It gave Yanobe a sense of spirit toward the earth that contained the new potential of “The Ruins of the Future”.

The artist had shucked off Atom Suit. He began to create a more universal and symbolic work that was not a device or tool to protect himself. That was the start of a new world of delusion for Yanobe, whose small, personal story that began with “The Ruins of the Future” would grow while coming in contact with the larger reality.